The immune system can control a relapsing form of malaria enough to avoid clinical signs of disease, but it doesn’t eliminate transmissible parasites from the body that may still be infectious to mosquitoes. That’s the conclusion of a study on a nonhuman primate model of Plasmodium vivax infection, which has implications relevant to malaria elimination strategies.

The results were published on September 19 online in PLOS Pathogens. The paper is a Featured Article this week.

“This study shows the explicit benefit of using a nonhuman primate model system to study the immune response, and relate the findings to human clinical cases and transmission. It is important to know that asymptomatic individuals may carry infectious gametocytes,” says senior author Mary R. Galinski, PhD, professor of medicine (infectious diseases) at Emory University School of Medicine, Emory Vaccine Center and Yerkes National Primate Research Center.

The parasite Plasmodium vivax is a major cause of malaria – a life-threatening mosquito-borne disease responsible for hundreds of thousands of deaths globally each year. P. vivax remains a major obstacle for malaria elimination, due to its ability to form dormant stages in the liver. These forms can become activated to cause relapsing blood-stage infections. Relapses in human patients remain poorly understood, because it is difficult to verify whether P. vivax blood-stage infections are due to new infections or relapses.

Researchers studied rhesus macaques infected with Plasmodium cynomolgi, a model of P. vivax, and assessed pathogenesis, host responses and circulating gametocyte levels during relapses.TheP. cynomolgi study was one of several projects conducted by the Malaria Host-Pathogen Interaction Center (MaHPIC), led by Galinski and including researchers from CDC, Georgia Tech, the University of Georgia and around the world.

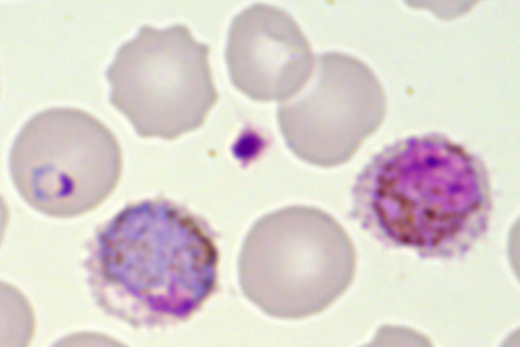

Compared to initial infections, relapses were clinically silent -- no fever or signs of inflammation -- and they were associated with a robust memory B cell response. Memory B cells are the immune system’s “reserve library” for antibody production. Relapse responses did result in the production of antibodies that were able to mediate clearance of parasites. Despite this rapid immune protection, sexual-stage gametocytes, which may be infectious to mosquitoes, continued to circulate.

According to the authors, the number of clinically silent relapse infections in humans, and their infectiousness to mosquitoes, remains largely unknown and should be evaluated carefully in the future. As a next step on the path to eliminating P. vivax and other relapsing malaria parasites, studies should identify the factors that influence relapse pathogenesis, immunity, and infectiousness to mosquitoes.

The first author of the paper is postdoctoral fellow Chester J. Joyner, PhD. Senior co-authors include F. Eun-Hyung Lee, MD, associate professor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine and director of Emory Healthcare's Asthma, Allergy and Immunology program, and Tracey J. Lamb, PhD, associate professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Utah School of Medicine.

The Malaria Host-Pathogen Interaction Center was supported in part by a contract from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHSN272201200031C). Research at Yerkes is supported by the National Institutes of Health Director's Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P51OD011132).