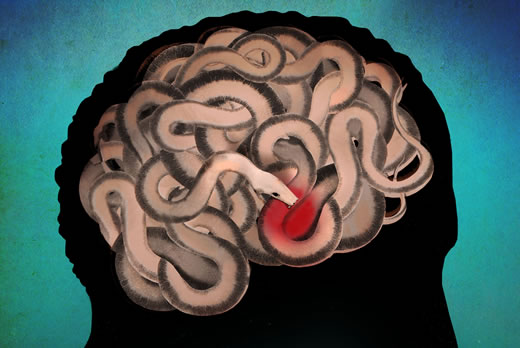

Fear in a mouse brain looks much the same as fear in a human brain.

When a frightening stimulus is encountered, the thalamus shoots a message to the amygdala — the primitive part of the brain — even before it informs the parts responsible for higher cognition. The amygdala then goes into its hard-wired fight-or-flight response, triggering a host of predictable symptoms, including racing heart, heavy breathing, startle response, and sweating.

The similarities of fear response in the brains of mice and men have allowed scientists to understand the neural circuitry and molecular processes of fear and fear behaviors perhaps better than any other response. That understanding has spurred breakthroughs in treatments for psychiatric disorders that are underpinned by fear.

Anxiety disorders are one of the most common mental illnesses in the country, with nearly one-third of Americans experiencing symptoms at least once during their lives. There are generalized anxiety disorders and fear-related disorders, which include panic disorders, phobias, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Emory psychiatrist and researcher Kerry Ressler is on the front lines of fear-disorder research. In his lab at Yerkes National Primate Research Center, he studies the molecular and cellular mechanisms of fear learning and extinction in mouse models. At Grady Memorial Hospital, he investigates the psychology, genetics, and biology of PTSD. And through the Grady Trauma Project, he works to draw attention to the problem of inner city intergenerational violence.

Kerry Ressler

"If you look at Kerry's work, it can seem like it's all over the place — he's got so many studies going on, and he collaborates with so many other scientists," says Barbara Rothbaum, associate vice chair of clinical research in psychiatry and director of the Trauma and Anxiety Recovery Program at Emory. "But they are all pieces to the same puzzle. All his work, from molecular to clinical to policy, fits together and starts telling a story." A Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, Ressler was recently elected to the Institute of Medicine — one of the highest honors in the fields of health and medicine. He was named a member of a new national PTSD consortium led by Draper Laboratory. And he recently appeared on the Charlie Rose show's brain series.

Panic attacks seem to tie the fear-related disorders together, he explained on Charlie Rose. Everyone experiences fear, which evolved as a survival mechanism, but it only rises to a clinical level when people are unable to function normally in the face of it. For instance, PTSD includes not only intrusive thoughts, memories, nightmares, and startle responses, but also the concept of avoidance, which may extend to other areas of the individual's life.

"There's a patient I've seen who was attacked in a dark alley," Ressler shared on the show. "Initially it just felt dangerous to go out at night, but after a while she grew afraid of men and couldn't go to that part of town. Then she couldn't leave her house, and finally, her bedroom. The world got more and more dangerous."