Emory University, which has become one of the landmark digital repositories of the Atlantic slave trade since it began hosting the renowned Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database in 2008, will host a public conference to discuss ways to further examine the history and stories that the brutal institution obscured for centuries.

“Archival Lives,” which runs Dec. 5-7, features historians sharing methods and archival knowledge of slavery from across the Americas and Africa. The event aims to connect archival findings to current public debate about reparations, racial justice and other issues.

“Americans are increasingly aware that slavery was a global phenomenon,” says Adriana Chira, an assistant professor of history who helped organize the conference with history professors Clifton Crais and Walter Rucker. “We want to think about evidence, and whose evidence we rely on when we write histories of slavery, so we can discuss that past in all of its rich complexity.”

“Going beyond the archives of the English-speaking Atlantic is imperative if we want to reckon both with the many ways slavery undergirded a range of different social systems, as well as with the myriad strategies that enslaved people developed to carve out social worlds for themselves against all odds,” she adds.

Growing access and digitized archives have upended how the history of slavery is learned and taught. Often, though, the primary documents focused more on the experiences of the traders and businesses, not of the enslaved people.

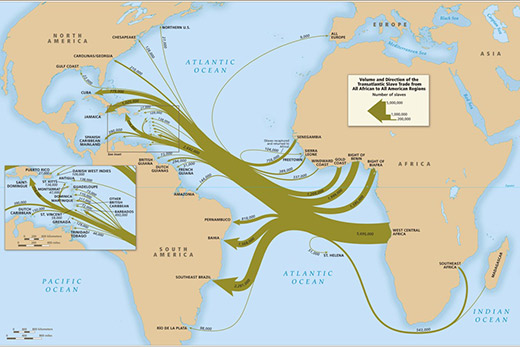

David Eltis, Emory professor of history emeritus and co-editor of the Voyages project, is one of the presenters. The new SlaveVoyages.org website contains four large databases, including 36,100 trans-Atlantic slave voyages and another 11,400 voyages from one port in the Americas to another, as well as personal details of 91,000 enslaved Africans found on board these vessels.

He asserts that the Voyages database “provides a framework without which a complete story cannot be told.”

“Trying to imagine scholarship on the slave trade … without knowing the size, direction and mortality/morbidity of the largest forced migration in history is rather like thinking of the conquest of disease without the discipline of epidemiology, or climate change without long-run data on temperature,” Eltis says.

Whatever the role of statistics in explaining the human experience, says Eltis, “one must know what a phenomenon is before one can think through the cultural, political or social consequences.”

Chira’s research, meanwhile, uncovered the role of enslaved people in the making and reform of the judicial system in Cuba by focusing on legal records there. Such records, like those from other archives of the Spanish-speaking world, reveal numerous instances of slaves turning to the courts for freedom and relief, with varying degrees of success.

“What many people forget is the Atlantic slave trade was at its most horrific at the same time as the rise of capitalism and liberal democracy,” says Crais, director of Emory’s Institute of African Studies. “We can reckon with that only if we develop conversations about those experiences.”

Conference presenters are sharing their papers with each other prior to the event. That will allow those conversations to begin during sessions, broadening the perspective on everything from the role of black African soldiers to questions of identity among mixed communities of indigenous people and those of African descent.

The workshop also features Guggenheim Fellow and Canadian poet M. NourbeSe Philip reading from her acclaimed poetry collection “Zong!” The book echoes the experiences of the 140-plus African slaves on the ship Zong, whose captain ordered their murder by drowning in 1781 for the insurance money.

“Recovering individual stories is part of reparations: as historians, it is our ethical responsibility to create room for voices that, more often than not, were supposed to be erased from the record,” Chira says. “We want to ask, with what we’ve learned, where should we go to further our critical understanding of that history.”