Spelman College President Mary Schmidt Campbell recently joined Emory University professor Kimberly Wallace-Sanders for a fascinating conversation about portraits of African American nannies, and how African Americans were represented in photography and images around the turn of the 20th century.

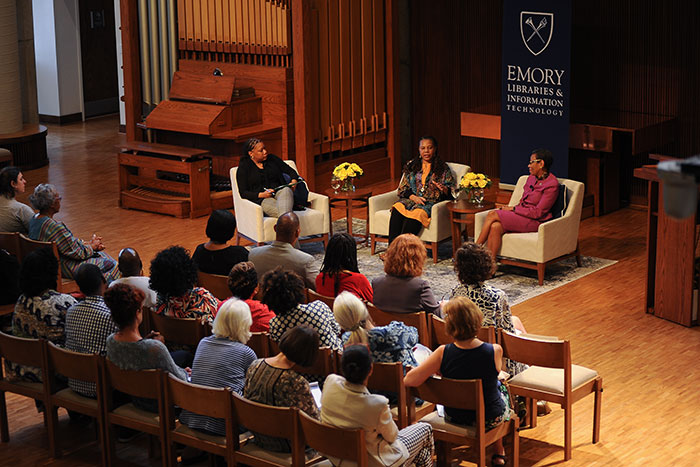

About 160 people attended the May 8 reception and exhibit viewing of “Framing Shadows: Portraits of Nannies from the Robert Langmuir African American Photograph Collection” at Emory University’s Woodruff Library and the conversation “Framing Shadows/Framing Lives” at Cannon Chapel.

The conversation, moderated by Rose Scott of WABE Radio, was inspired by the “Framing Shadows” exhibit, on display through January 2020 at the library’s Schatten Gallery. The photos of African American nannies posed with the white children they cared for represent a portion of the 12,000 images in the Langmuir collection held by the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library.

Wallace-Sanders, associate professor of American studies and African American studies at Emory, curated the exhibit, which provides insights on the experiences of the often anonymous 19th and 20th century African American women and girls who served as child care providers for white families.

There was a moment of serendipity at the reception when Barbara Coble, partnerships manager with Emory Graduation Generation, showed Wallace-Sanders an old photo of her great-great-grand-aunt in a domestic uniform, holding a white child. Wallace-Sanders was thrilled; she had hoped the exhibit would prompt African Americans with relatives who had served as nannies for white families to contact her with photos, diaries or just stories about those women.

Wallace-Sanders, who has studied the mammy stereotype since her college dissertation days, wrote two books on the topic and is completing a third book on portraits and the nanny/child relationship that closely aligns with the “Framing Shadows” exhibit.

The author of a recent biography on black artist Romare Bearden and co-author of two other books on black arts, Campbell began her career in the arts as a museum director and curator at the Studio Museum in Harlem and also served as dean of New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts for 20 years.

Campbell said she was struck by the stark difference between the portraits of the African American nannies who were required to pose with their young charges, and the photographs assembled by W.E.B. Du Bois for the “American Negro” exhibit at the 1900 Paris Exposition.

“Those photos were all taken by black photographers in the wake of Emancipation, and they portray this huge world of educators, pastors, musicians,” Campbell said. “These feel like, even though the world is constrained for these women, they were able to create an image for themselves. There are still elements of self-determination and self-expression.”

Campbell and Wallace-Sanders discussed how some of the nannies in the Langmuir portraits wore something – a comb in their hair, a piece of jewelry, special trim on their uniforms – that expressed their individualism or a bit of defiance.

“There’s a visual dissonance, so if you’re expecting to see stereotypical mammies, that’s not what you see at all,” Wallace-Sanders said. “You see real black women with real lives who left their children and their families behind to take care of someone else’s children all day long. And that’s what gets me every single time.”

Some of the domestic workers were “companion nannies,” African American girls as young as 13 hired to care for the children of white families to avoid the trauma of an older nanny passing away. The idea was that the nanny and the children would be playmates and “grow up together,” Wallace-Sanders said.

“This is a rescue mission for me. Someone has to rescue these stories and rescue these women from obscurity. That’s what drives me,” she said. “No one who sees a photo of a little black girl taking care of three little white children is going to forget that image.”

In contrast to the moving images in the “Framing Shadows” exhibit, Campbell noted, the mammy stereotype around the turn of the 20th century was pervasive, in films like “Birth of a Nation” and “Gone with the Wind,” in blackface performances, in advertising and many other mediums.

“At the same time these photos were taken, the country was manufacturing these mammy images that were very derogatory, that were caricatures,” Campbell said. “This is a very rich time to be unearthing these images.”

Cynthia Spence, associate professor of sociology at Spelman and director of the UNCF/Mellon Institute Programs, was drawn in by the efforts to make the women’s stories known. “The work that Kimberly is doing is amazing and so important,” Spence said. “She’s uncovering the stories of these women who in many ways were made to be invisible.”