As a graduate of Cambridge University in 1968, Salman Rushdie was among a generation of students who confidently believed that “the battle of free expression had been won.”

In fact, throughout most of his adult life, Rushdie recalled feeling assured that the struggle for free speech was over. “It was no longer necessary, because we already had it,” the acclaimed author reminisced before a packed audience at Emory’s Glenn Memorial Auditorium during his campus talk Sunday night.

But over the years, rising attacks upon free expression reported around the world would prove him wrong — from death threats against Rushdie himself in 1989 for publishing “The Satanic Verses” to last month’s murders of cartoonists at the satirical French weekly Charlie Hebdo and Saturday’s attacks at a free speech event and synagogue in Copenhagen.

These are not good days for freedom, Rushdie observed. “If you look around the world, you see the ideas of freedom — freedom which contains the sense of carefree-ness — seem everywhere in retreat, hounded by guns and bombs,” he said.

But here in America, threats upon free expression are “beginning to be the greatest where they should be most defended, that is to say within the walls of the academy,” Rushdie said.

“And the people most willing to sacrifice, or limit, this fundamental right are young people,” he added.

Given that landscape, Rushdie issued a rallying call to campus communities everywhere — and especially university students — urging them not to take such freedoms for granted.

“These rights have been hard won, hard won,” he said. “Do not easily give them up. Do not give an inch.”

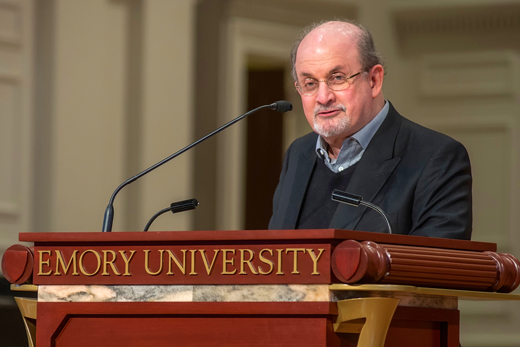

Rights to freedom of expression “have been hard won, hard won,” acclaimed author Salman Rushdie said in his last public lecture as University Distinguished Professor. “Do not easily give them up. Do not give an inch.” Photo by Tony Benner.

Reflections upon a decade at Emory

Rushdie’s lecture marks a poignant milestone, as the award-winning author and human rights advocate concludes his final year as University Distinguished Professor in the College of Arts and Sciences.

In introductory remarks, Emory College of Arts and Sciences Dean Robin Forman acknowledged Rushdie’s broad contributions to Emory, a relationship that began when Rushdie delivered the Ellmann Lecture in Modern Literature in 2004.

In 2006, Rushdie was named Distinguished Writer in Residence in Emory’s Department of English and placed his archive with Emory’s Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library (MARBL) — a relationship that will continue, he said.

Working out of the Department of English, Rushdie’s annual visits to Emory created expansive opportunities to engage students and the broader academic community through venues large and small, from public lectures to classroom appearances, faculty forums to literary events.

In his role as Distinguished University Professor, Forman said that Rushdie has taught or contributed to a wide range of courses stretching across the humanities and social sciences into professional schools through disciplines that have included literature, creative writing, film and media studies, philosophy, psychology, history and Middle Eastern and South Asian studies.

But beyond Rushdie’s more serious role as an educator and champion of human rights, “the last decade has been great fun,” Forman noted, praising the author for sharing his mischievous wit, passion for all forms of literature and an “aesthetic audacity and moral courage that will inspire us for decades to come.”

In introducing Rushdie’s final public lecture as University Distinguished Professor — a bittersweet task, he noted — Forman announced that the celebrated author will be awarded an honorary doctor of letters degree at Emory’s 170th Commencement ceremony in May, where Rushdie has also accepted an invitation to present the keynote address.

“We are better because of this relationship,” Forman said. “Salman has consistently inspired us, provoked us and encouraged us to be our best selves.”

Challenging a culture of timidness

Too often, modern attacks on free speech have been met by “a new kind of timidness,” Rushdie asserted in his lecture, describing a culture that increasingly seems to believe that offending people must be avoided at all costs.

To illustrate, he described a recent decision at Mount Holyoke College, an all-women’s school in Massachusetts, to cancel a performance of Eve Ensler’s feminist classic “The Vagina Monologues” because “by defining women as people with vaginas, the play discriminates against transgender people who do not,” he explained.

Smiling, Rushdie said, “Now look, I’m in favor of good manners. I think I’m a quite well-mannered person myself. I like good manners in those around me, my family and friends and colleagues. But to equate social good manners, the way we interact with each other, with the liberty to say what one thinks, even if people don’t like it, is to make a false comparison.”

“Ideas are not people,” he said. “Being rude about an idea is not the same thing as being rude about your aunt.”

“One can choose whether or not to consume such things. If you don’t like the book, close the book. If you don’t like the movie, don’t go to see the movie. You are free as the makers. They have the right to speak and you have the right not to listen if you fear it will upset you.”

“What you don’t have is the right to use your alleged offended-ness as a reason to stop other people from speaking,” he added.

To put it simply, the defense of free speech must begin with what offends you, Rushdie explained.

“That’s not the boundary, that’s the starting point,” he said. “It’s really easy to defend the right to speak of people that you obviously agree with or to whom you are indifferent.”

The true test of tolerance is when somebody says something that you disagree with, but you can still defend as free speech, he noted.

That is democracy, Rushdie said. “It’s not polite. It’s not a tea party. It’s a rough-and-tumble affair. It’s an argument. It’s permitting others to say what you think is unsayable … If you want it, that’s the price of the ticket.”