Following the mindset of W.E. Dubois, Erskine, professor of theology and ethics at Emory's Candler School of Theology, acknowledges that the plantation is "the sociological reality that Africans were brought to in the Americas, whether in the American cotton fields or the sugar cane fields throughout the Caribbean."

It is out of this location that plantation church emerges, "as people of African descent brought their religious practices to this reality" says Erskine. While both regions share the plantation, Erskine's research emphasizes the Caribbean as the starting point of black religious experiences in the Americas. "Slaves began to arrive in the Caribbean in 1502, more than 100 years before slaves set foot in America," says Erskine.

While black religious experiences have developed differently in the United States and the Caribbean, "Plantation Church" looks to their similarities and offers an intriguing approach to scholarship on the American "Black Church" experience by situating its origins in the Caribbean.

Survival at the Heart of Plantation Church

When addressing all of the ways in which slavery dehumanized individuals, Erskine continues to return to the question: How did slaves survive?

After traveling across the Atlantic "packed like sardines" to a foreign environment that greeted them with enslavement, Africans looked to the continuation of African culture as a means for survival, Erskine says.

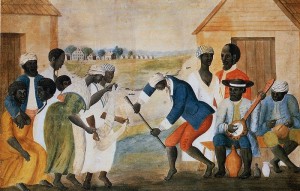

Within African culture, many religious practices supplied the forms of transcendence, which helped lift slaves out of the conditions of slavery, he says. Dancing and drumming served as occasions where slaves could commune and actively participate in forms of liberation. For Erskine, forms of African religious practices such as these remain at the heart of the plantation church.

While situating African religious practices at the heart of plantation churches, Erskine also notes the critical role Christianity plays in the formation of plantation churches.

"The only religion that was authorized on the plantations was Christianity," says Erskine. "In many ways, slaves were able to merge and blend their African practices with Christian practices as another means of survival."

To do so, Erskine emphasizes the openness maintained by slaves. Because slaves were open to incorporating the Bible to their religious practices, while also upholding their memories of Africa, the plantation church formed, providing a means for survival and a place to dream.

Africa, Jesus, Family

Noel Leo Erskine

Erskine returns to themes of Africa and Jesus throughout the book. In his introduction, he offers his grandfather and father as representatives of these two themes and their relationship to black religious experiences in the Americas.

Erskine's Grandpa Tata represents the notion of "Pure Africa." He connected the spiritual to the natural landscape. Erskine remembers sitting with his grandfather by the spring where his grandfather would tell him to be quiet and listen to the birds and the stream. For slaves, the rivers or the fields were reminders of Africa and forms of worship occurred there.

Alternately, Erskine recognizes his father as a man who accepted Jesus over Africa, who went to seminary due to his understanding of Jesus as the necessary means for liberation. Within the book, Erskine struggles with how Africa and Jesus help construct the plantation church, whether in opposition or united.

Church Outside of Church

While slaves were encouraged to go to their master's church, Erskine points out that these worship services typically were not adequate for the slaves. The formal setting remained closed to African practices, he says, and early participants continued to make space and time for their own culture, their own religious practices.

The Old Plantation, 18th century American folk painting via Wikipedia

Erskine feels that the real experiences of plantation churches occurred primarily outside of the formal services we know today. "Slaves created church outside of the church. They would steal away to the forest, brush arbor, the stream, there they would do their thing. They would commune with spirits, commune with God," he says.

Even today, Erskine feels that the notion of creating church outside of church can still be seen. He notes that until recently, African drumming and dance continued to be too African for formal church services, yet people still made occasions to be drawn into the spirit through these practices.

"Even when you think you close the door to Africa," he says, "I think once the people gather, African culture and religion seeps in."