As director of Emory's Ethics and the Arts program — and a lifelong photographer and filmmaker — Carlton Mackey is used to exploring the questions that intrigue him through an artist's lens.

So as he prepared to become a father for the first time, questions of skin tone and identity, beauty and culture came to captivate him as never before: Will this child identify as biracial? Will he identify as black? What is blackness? What does skin tone mean in the search for identity?

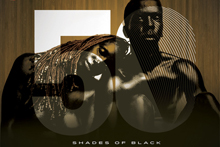

50 Shades of Black

His response was to embark upon a deeply personal exploration of the topic, which has resulted in "50 Shades of Black" (self-published, 2013), a multi-disciplinary art project funded, in part, by a grant from Emory's Center for Creativity & Arts, that investigates the intersection of skin tone and sexuality in shaping identity through both a book, a website and traveling art exhibit.

It was curiosity — and an eagerness to pursue the questions that fascinated him — that first brought Mackey to Emory; he arrived in 2002 to pursue a Master of Divinity degree at Candler School of Theology, joining the Center for Ethics shortly after graduation.

Today, he serves as assistant director of the D. Abbott Turner Program in Ethics and Servant Leadership (EASL) and assistant coordinator of undergraduate studies, and joins EASL Director Edward Queen this fall in co-teaching a new class, "Art and Social Engagement," which links Emory students with local nonprofit partners to create public art projects.

Emory Report caught up with Mackey to discuss the evolution of "50 Shades of Black," which will be the focus of a public exhibition at the Center for Ethics next February.

Where does your story as an artist begin?

My roots go back to Southern Georgia. I was born in Jesup, Georgia, and raised by a mom (Burnell Mackey) and dad (Carl Mackey) who loved me dearly. When I was 4 years old, my mom passed away after battling cancer. After that, I moved to Blackshear, Georgia, to live with my grandmother, Pearl Taylor — the single most important female figure in my life, outside of my mom, who spent my formative years rearing, shaping and molding me.

As an adult, I have a new set of eyes for understanding how she influenced me as an artist. But it doesn't look like painting or drawing or making films. She got as far as the sixth grade and worked hard her entire life — so no, not a lot of art in that sense. But I've come to understand some of the key ingredients for being a successful artist are thinking outside the box, being resourceful. Creativity can flourish more when there are limitations than when there is excess, I think. That's what she showed me day after day. I use that as an artist.

As an undergraduate at Tuskegee University, you majored in electrical engineering. How did you make the leap to ethics?

In college, I wasn't a 4.0 dude, but I was active, serving as SGA vice-president and president my junior and senior years, respectively. I interviewed well, apparently, at a career fair for a job with a software company out in California called PeopleSoft and was offered a position. I went out there for training, which is where I met my wife, Kari, then they brought me back to Atlanta. That was 2002, an era when dot.coms were struggling. And I lost my job.

Throughout my life, religion had played a very formative role for me. Both of my parents were very faithful Christians and I was raised in the church. When I lost my job, it led to these bigger life questions. Those questions led me to Candler School of Theology. I didn't even know there was a place you could go to ask these questions. But it was the most natural next step.

What did the experience give you?

The not-straight-forward answers to questions. It's a program very much built around exploration, and it was a challenging one. I had all kinds of other crises of faith — like, people didn't refer to God in the masculine, I'd met gay seminarians, what does that mean? But it became the most liberating experience. I was able to see difference among people who were extremely faithful, and then I was able to form very, very strong relationships with people who blew out of the water my narrow understanding of these things.

How did you come up with the idea for the "50 Shades of Black" project?

Before I had my son Isaiah, I'd never dated anyone who didn't look like me. But I fell in love with my wife (Kari, who is white). When I was going to become a father, I started having these questions: What is this kid going to look like? Is he going to identify with me? Am I going to identify with him? Is he going to be black? What is blackness?

When I saw him, all that went out the window, didn't even matter. But the root of those questions are very real and continue to be very real, not only for parents, but for children who look like him, historically, who will go through life with people asking, "What are you? Where are you from?"

How did the idea begin to take shape?

An artist's mindset took over. I started thinking about blackness and sexuality on a spectrum. At the time, everybody was talking about "Fifty Shades of Grey," so decided to flip it and talk about "50 Shades of Black."

I created this (poster) of faces that show the spectrum of human skin tone — from Dorothy Dandridge to Djimon Hountsu — and put it out on Tumblr, just art for art's sake. But then I thought, "This is about the complexity of skin tone. I could start a deep, cultural conversation." Then it kind of went viral.

When did this become a book and website?

It started resonating with people. I received emails, personal stories. So I quickly started soliciting more thoughts, seizing opportunities along the way. You talk about ethics and the arts, and you are really using art to have conversations about complex questions and realities. The collection of emails and comments became a manuscript of scholarly essays, personal narratives, poems and photographs. Many of these people are from Atlanta, some are Emory students, so this really is community-built.

Where do you take the project from here?

I think the story will continue, perhaps with a second volume, with me being nimble and responsive to things around me, as well as doing things that I couldn't have imagined — a possible exhibit and tour.

You initially wanted to explore these questions for your son — did you accomplish what you were after?

If nothing else happens, I'm wildly satisfied. I want him to be free to explore and to also free up other people and give them space for liberty in their own exploration. And I think this book, the kind of energy around it, does that. Just him knowing that I take him and these conversations seriously, and I'll always be able to show him that or tell him that, is really what this is about.

Suggest an Emory Profile

Do you have an Emory Profile suggestion? Send it to emory.report@emory.edu. Emory Report is always seeking faculty and staff with interesting personal or professional stories to spotlight in this regular feature series.