Bobbi Patterson is consumed with the task of preparing Emory undergraduates to encounter the world and their place in it. Students in her religion and ecology class this past fall interspersed their readings with Patterson-led hikes around the Emory campus, to Atlanta’s renowned Auburn Avenue district and even camping in North Georgia. Some of them weren’t looking forward to it, but that changed.

Here’s how Patterson, a professor of pedagogy in Emory’s religion department, describes a typical class:

"We stand in a circle, 25 students and me, their teacher. Our class is in Religion and Ecology and today’s lesson happens within our 135-acre campus green space, Lullwater Park.

"Some students scope out the landscape around us—invasive privet and indigenous white oaks. Others shift from right foot to left, shuffling in the sandy soil deposited by storm surges through the South Fork of Peachtree Creek beside us.

"My eyes meet the few looking directly at me. We exchange tentative anticipation over the contemplative practice we are about to begin. Even after six years of teaching this class, my gut knots as we take a more complicated practice into our repertoire. We are moving again from theory to practice in order to return to theory; so goes the cycle."

Patterson's class explores the relationship between nature, religion and culture—and then much more. Students begin by examining Christian and Buddhist conceptions of nature and human relations with the surrounding world, its natural histories, its ecosystems, its familiar and unfamiliar places. Then they go out to explore, contemplate and learn more.

"We learn the stories of this place," says Patterson, meaning the Emory campus and surrounding Atlanta and woods of North Georgia. And you can't learn a place unless you inhabit it, or as Patterson calls it, "re-inhabit it."

Students supplement their readings with inquiry-driven exercises in which they explore the relationships and responsibilities among the living earth, plants, animals and humans. They hear tales of Creek and Cherokee, and the scandalous Trail of Tears.

They examine issues such as climate change, regional urbanization exposing structural racism especially in transportation and patterns of local development. From a classic Buddhist forest dweller, to the early Christian mothers and fathers, the variety of viewpoints puts students in dialogue with long-established religious traditions, questions of human and more-than-human justice, and contemplative practices.

"Every year I think this will never work," says Patterson of the experience of leading undergraduates on this inner and outer journey.

Engaging the whole person

"When we're hiking, we have to be attentive to the person behind, to the person in front," Patterson says. "You can't make your own pace, there can't be gaps. We have to help each other. They become very mindful of each other."

That awareness of the other carries over into group discussions, when students become mindful that to have true intellectual exchange, one must make space for the other person's words and ideas.

"Some of the students said 'This is a part of college where I get to think about my whole self and integrate my intellectual life and what I'm reading in texts into my life and my future,'" says Patterson. "And they are wanting more of that."

Understanding living systems

Patterson's quickening of imagination around the concept of resilience happened as a result of shared conversations with Lance Gunderson, environmental studies professor at Emory and co-editor of the 2002 book, "Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems."

"He [Gunderson] shared with me some models of living systems," says Patterson. "These models always include periods of collapse or breakdown or destruction. And there has to be the capacity within these systems to re-gather the broken pieces and move them into the next cycle of life." And that re-gathering quality is part of the built-in resilience of the system, she says.

"Panarchy" reaches beyond ecosystems into human systems, which struck a chord with Patterson, awakening her understanding that the contemplative religious traditions such as Christianity and Buddhism embrace the idea that life will bring suffering. "It's a part of what happens to us," she says.

But these religious traditions also provide a set of skills "for moving through suffering to a kind of re-gathering of resources and fulfillment of life. Those skill sets are related to resilience," she says.

Shifting toward resilience

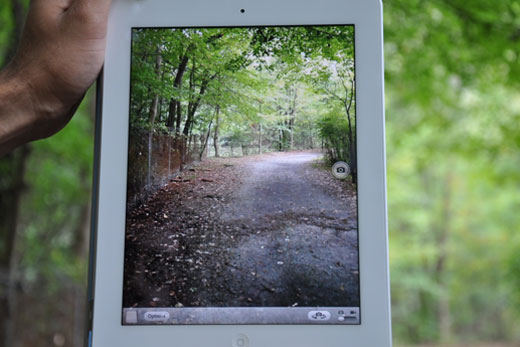

Students pick a spot outdoors, go to that same spot every week for contemplation, and watch changes in natural systems. Photo courtesy of Saagar Sheth.

Patterson believes that ultimately resilience can be taught. "I'd like to de-mystify resilience and talk more about it as an attitude and perception by practicing the skills. It's a doing-generated experience," she says.

Students in her class learning this skill by picking a spot outdoors, going to that same spot every week for contemplation, watching as natural systems break down in the fall season.

"They see death of the natural systems and they write about it," says Patterson. "They see the collapse, but they notice the resilience of the place because they're in the practice of going there every week, observing it carefully as much on its own terms as they can."

And students find themselves at the end of the term "oddly attached" to the place of their observations, "because they see a change." Another way of thinking about suffering, says Patterson, is change.

"What they notice is the beauty in change, the possibility in change," she says. "They can also pay attention to the grief in change and notice that they can move through it." They can learn resilience.

Why teach resilience? "A liberal arts education is about preparing people for life," says Patterson. "These are qualities that life has: that within these systems, there will be tough times. Resilience is the ability, perception and awareness to gather the pieces and move through it, grieve when you need to grieve and process, then reach out to others, realizing you're not alone. That's a key dimension of a liberal arts education.

"I'm a big advocate of remembering that in the United States, the liberal arts early on were tied to democracy," she says. "Democracy is a very fragile thing. It is always in the process of breakdown, collapse and rebuilding. That quality of resilience is what helps sustain democracy. Our citizens really need to be resilient, because we have to be able to come back together."